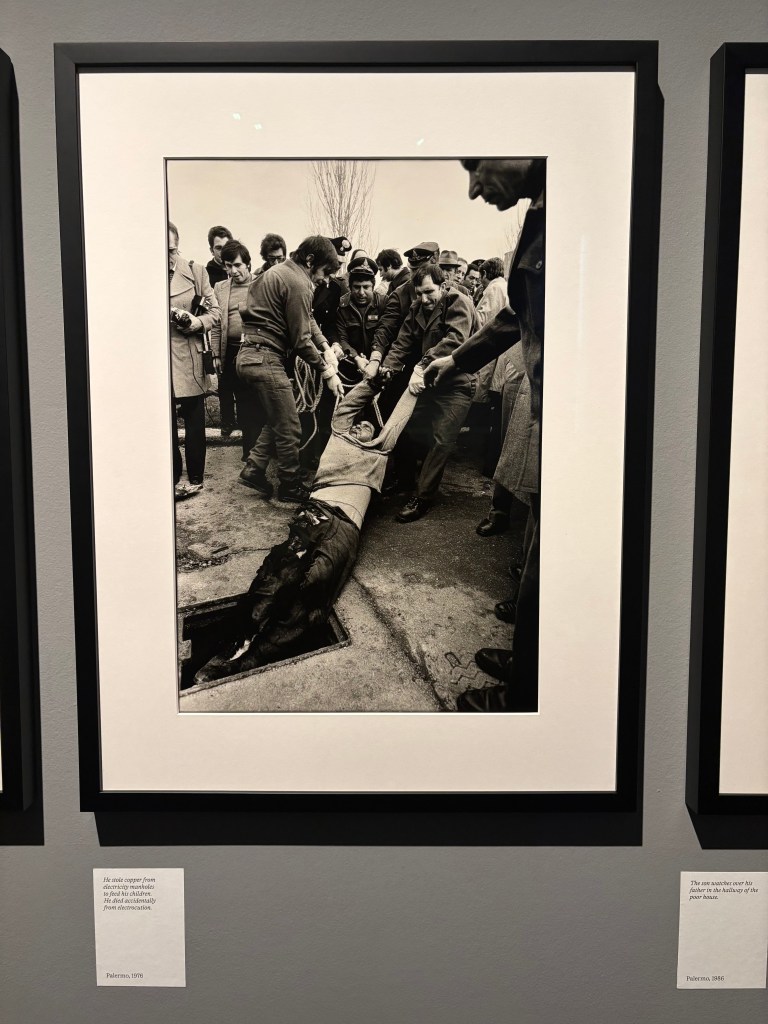

He stole copper from electricity manholes to feed his children. He died accidentally from electrocution. Palermo, 1976.

The photograph by Letizia Battaglia is a heartbreaking proof of the brutal truth of Mafia killings in Sicily. Her black-and-white images are pretty effective in showing the inhumanity of such killings, at the same time showing the victims as people so that the viewer can understand the terrible effect that organized crime has on people’s lives. The composition, first and foremost, pays attention to the lifeless body, the people who come to his rescue, and those who watch the scene, which is somewhat chaotic but at the same time relatively ordered, as if it reflects the collective mood of Palermo. She documents the moment in its most basic form, without any post-processing, to show how it feels to be a part of the moment and not just watch it. Battaglia documented these tragedies to undermine the Mafia’s social control and also to remember the victims, thus using photography as a tool to fight evil and demand justice.

Khalsa neighborhood. The girl with bread. Palermo,1979

Letizia Battaglia’s photographs are a clear example of a work that aims at showing the public the violence carried out by the Mafia in Sicily, without forgetting the people that have been affected by it and the fear that was felt throughout the region. The use of black and white photography in her work makes the crimes seem more real in a way that other colors cannot. On top of that, the use of high contrast, natural lighting, and very precise framing to capture the moment makes the viewer feel like they are actually standing in the middle of Palermo’s turmoil. Her images are not only beautiful but also purposeful, having docmented a part of history and fighting against the mafia at the same time. In a way, the photographs are part of a series, and they are meant to make the viewer understand the process of the cycle of violence and resistance in the context of the Mafia’s influence that was not only limited to its members but also extended to the entire Sicilian society. The lack of strict thematic divisions in the exhibition is quite fitting for the chaotic and unpredictable life of Palermo and the way Battaglia encountered the images during the project—without any distinction between violence, sorrow, and daily life. This structure makes the collection look and feel more cohesive and emotional. Also, the written context increases the effectiveness of the work, which gives historical and political information that relates to the images and the viewer. Knowing that Battaglia worked in risk, and knowing the importance of her production in the context of the world, makes the photographs become not only a way of documenting, but also a cry for justice, for the memory of the victims.